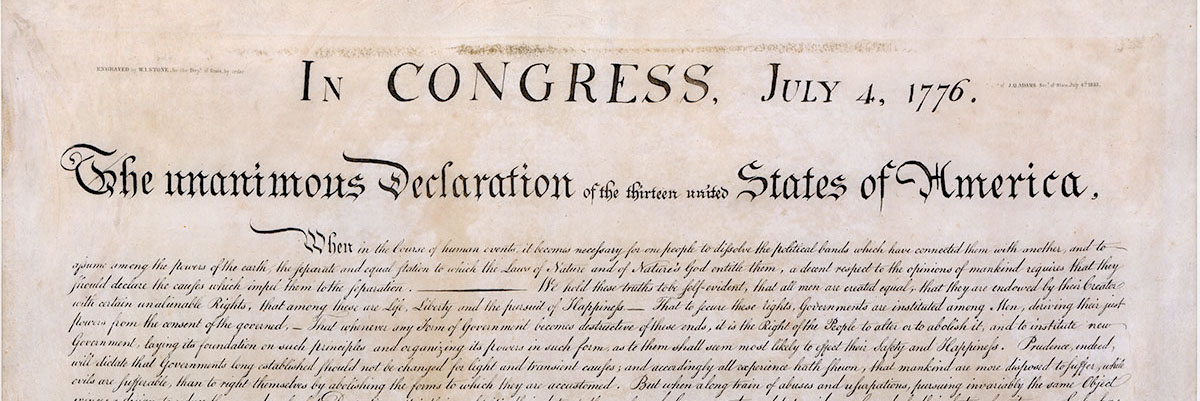

“WE HOLD THESE TRUTHS TO BE SELF-EVIDENT: THAT ALL MEN ARE CREATED EQUAL; THAT THEY are endowed by their creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” The philosophical underpinning of the great American experiment. Words to stir the soul.

And perhaps that’s enough. Maybe it’s too much to expect a rallying cry, a declaration of independence, to be internally consistent as well as inspiring. Still, as I recall these words after a long life watching the turbulence of American governance, I find myself pondering the tension in the rights Jefferson and his colleagues guaranteed to the citizenry of the new nation.

For the purposes of this essay, I’ll set aside the most glaring injustices these guarantees ignored: the protection of slavery, the disenfranchisement of those who did not own property, the callous disregard for women, and the implicit hostility toward the peoples who had occupied the continent for millennia before the arrival of the first European. These prejudices were deep-seated and corrosive; after more than two centuries, they continue to gnaw at the foundations of our system, demanding solutions we still struggle to impose or even identify.

But I want to focus on an even more fundamental contradiction in Jefferson’s words: the antithetical concepts of equality and liberty.

Thomas Jefferson, primary author of the Declaration of Independence. By Jacques Reich, Library of Congress.

“All men are created equal.” Is that true, as Jefferson claimed? Clearly not. Even in the eighteenth century, it was obvious that people were born with different intellectual and physical abilities. Besides the reality of birth defects, there was the simple reality that some people were bigger, stronger, prettier, more thoughtful, more dexterous, more inventive than others. Add to that the part that blind luck plays in success, the hard reality that some talents are worth more than others in the marketplace and that this scale of value shifts over time. The abstract computational and engineering aptitudes that were necessary to build the modern computer could well have condemned their owners to prison or execution in another era. For uncounted millennia, the need for raw physical strength, speed, and endurance were crucial to the survival of any social group; today, they are relegated almost entirely to sports arenas. A talent for training and managing horses was once a valuable commodity; these days, it’s a novelty with little practical value. The capacity to read and write, indispensable in modern American culture, was useless over most of the span of human history. The standard of feminine beauty has changed over and over again, to the advantage of some and the disadvantage of others.

While there have been many efforts to interpret Jefferson’s statement in a way that bears some faint resemblance to the facts, to twist the definition of the word “equal” until it fits the system we’ve built, we are not created equal, nor do our innate talents have equal economic or cultural value. It’s simply not true that we all begin the race at the same starting line or that the rules of the contest apply without exception or modification to all the contestants.

Nor, in spite of all our high-flown rhetoric, does our system offer anything like equality of opportunity for advancement. The hard numbers show that Americans born into poverty have practically no hope of rising to great wealth, while Americans born with silver spoons in their mouths are likely to enjoy a position in the de facto aristocracy all their lives. The social and economic hierarchies Americans have roundly condemned in other societies have taken a slightly different form in our culture but are nearly as virulent and entrenched.

The right to liberty guaranteed us in the opening lines of the declaration would seem to be unrelated to the notion of equality, and, in theory, they may be quite separate, but in the real world, the American ideal of liberty isolates the individual, emphasizing competition over cooperation and, by implication, placing the responsibility for any failure, any inequity, directly on the person who suffers it rather than recognizing the stark differences in genetics, innate talents, family backgrounds, income, and education that enforce status and economic position in modern American society.

The men who ratified the declaration can, perhaps, be forgiven for advocating personal freedom with such force— they were, after all, the scions of a long lineage of people who had been oppressed in the name of an unending succession of monarchies and dictatorships. Still, a few more words on behalf of brotherhood might have been appropriate. It’s worth noting that, after their presentation of a revolutionary theory of ethical government and the litany of grievances that followed, they waited until the last sentence of the document to mention their commitment to each other— “we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor.”

In the years, the decades, the centuries that followed, the mandate implicit in that pledge was often lost, while the pursuit of individual liberty continued with a white heat. The conflict between the concepts of liberty and equality has been at the root of many of the nightmares that have arisen from the American dream.

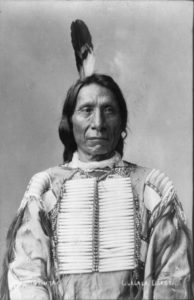

For the first century of the republic, there was one safety valve that lowered, ever so slightly, the pressure created by the collision of the two ideas. That safety valve was the myth of frontier. I say “myth” because there was no real frontier, if, by the word, we meant land that was unoccupied and available, without moral or physical challenge, to anyone who claimed it. There were long-term residents in the New World when Columbus first hit the beach, residents who proved to be unwilling to cede their rights to invading hordes of Europeans. Subsequent waves of immigrants convinced themselves that these original occupants had no right to the land, freeing themselves of legal and ethical constraint and opening the “golden door” of opportunity for millions of people, some of them fresh from the Old World, others simply tired of dealing with the entrenched power brokers of the New. For generations of Americans, there was always an alternative to the constraints of “civilized” society: the “free” land to the west.

Of course, that land was anything but free. Claiming it was a dangerous, expensive gamble that failed more often than it succeeded. Still, the choice was there, and it offered an escape from the economic and social constraints of the eastern establishment. The myth of frontier bolstered the American ideal of individual liberty.

In 1893, the historian Frederick Jackson Turner announced that the frontier as a demographic phenomenon no longer existed in America. The frontier, he argued, was “a gate of escape from the bondage of the past. . . . And now, four centuries from the discovery of America, at the end of a hundred years of life under the Constitution, the frontier has gone, and with its going has closed the first period of American history.”

Turner’s analysis has been criticized for its emphasis on English, Germanic, and Scandinavian influences at the expense of other ethnic groups like the French, Spaniards, native Americans, and Chinese; it has been attacked for its failure to appreciate the central role of slavery in American culture; it has been condemned as paternalistic and racist. There is some ground for all these points of view and possibly even more justification for criticizing Turner’s tacit assumption that the land on the continent was somehow unoccupied and “free.”

As I see it, Turner unintentionally offered an accurate description of frontier, not as objective reality but as a cultural touchstone— a myth. Does that matter? Is there anyone who doubts the power of myth? Frontier was the driving force behind American expansionism, a nation’s “Manifest Destiny,” even more powerful in defining our character than the slave-owning culture we abetted. The possibilities it seemed to offer captivated hundreds of millions of people around the world and persuaded many of them to emigrate to the New World. When that myth disappeared, the clash between the guarantees of liberty and equality had no other outlet.

The first sixty years of the twentieth century were full of distractions that deflected American attention from this fundamental conflict. Generations united to fight wars and economic catastrophe, but, even as they struggled to surmount those challenges, the underlying tension between the guarantees of liberty and equality drove wedges between major segments of American society.

For the last thirty years or more, we’ve been largely spared the kinds of great historical calamities that occupied our fathers and grandfathers. Freed of mortal enemies, insulated from the most destructive fluctuations of our economy, we find ourselves confronted again with two ideals that were proposed as a foundation of government but probably can’t exist together in anything like pure form.

It seems to me that liberty and equality are inversely related, at least in a nation that has no empty spaces left with which to accommodate its malcontents. I’m not sure whether the two exist in a zero-sum relationship, but I am pretty certain that, as one increases, the other tends to decline. To the degree that is true, the exuberant language of the Declaration of Independence created a conflict of expectations that echoes down through history.

The crowd at Gettysburg for Lincoln’s address. The President is bareheaded and seated just to the right of the flag in the background. Photographer unknown, Library of Congress.

Almost a century after Jefferson’s words were ratified, another American leader spoke of “a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.” He wondered whether “that nation, or any nation, so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure,” implicitly recognizing the clash between the two Jeffersonian ideals, liberty and equality. The magnitude of that conflict was reflected in the carnage of the Civil War, the violent confrontation between one man’s liberty to hold another human being as property set against the right of every man to be free. Two radically different conceptions of individual freedom and equality.

In 1865, the nation ratified the thirteenth amendment to the constitution, which guaranteed liberty to a people that had been enslaved. The question of the equality of those people was not addressed. It strains America’s social fabric to this day.

The commitment to the ideal of equality constrains liberty. The commitment to the ideal of individual liberty undermines equality, whether we prefer to focus on some sort of philosophical equilibration of intrinsic human importance or a more pragmatic assessment of the social value of each individual. There is a balance to be struck, a balance so fragile and ephemeral that it may never be found. The great declaration aspires to something that may never be achieved, that may not be possible to achieve.

At Gettysburg, Lincoln said our work was unfinished, that there was a “great task remaining before us.” Had he survived the war, he might well have recognized just how much greater the task was than even he anticipated. In that moment, at the height of the blood-letting, I don’t think he expected to reach the goals that rang out in the declaration. His aim was modest in comparison— simply to preserve the union.

Nearly 160 years later, the greater task remains. I think it’s fair to say that we’re closer to a humane balance between liberty and equality than we were in 1863, but the venom in the debate these days leaves the question Lincoln posed unanswered: Can a nation committed to striking that balance long endure? I don’t know. But I join the Great Emancipator in the prayer he offered on that terrible battlefield— “that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.