Remarks on the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of the Cheyenne chapter of the Audubon Society

HISTORY HAS SOME STRANGE TWISTS. THE NAMES THAT ARE SO OFTEN UP IN lights in our textbooks and memories weren’t always as influential as the record would have us believe. I was taught that James Watson and Francis Crick deserved complete credit for deciphering the structure of the DNA molecule.

Even today, the name of Rosalind Franklin is largely forgotten, even though she refined the equipment and techniques that ultimately revealed the nature of the double helix and first recognized the symmetry in the molecule, the difference between dried crystalline DNA and the more important hydrated form, and the fact that the order of base pairs on the ladder didn’t affect the overall structure of the molecule. These were all crucial insights into the function of DNA.

The labs at Radio Corporation of America— RCA— have long been given credit for the invention of the television, which the company’s CEO essentially stole from the true inventor, Philo Farnsworth. By the time I started watching TV, Philo’s name had become a punchline while RCA was reaping billions in profits.

Guglielmo Marconi is remembered in the texts as the inventor of the radio, even though Nicola Tesla held earlier patents for systems that transmitted information with radio waves.

Like the record of technological advances, the histories of great political transformations, breakthroughs in social justice, and innovations in the arts are often told through the biographies of a handful of luminaries whose reputations have outrun their actual contributions.

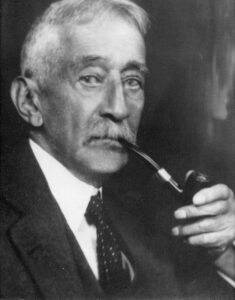

Theodore Roosevelt portrait by John Singer Sargent.

And so I come to Theodore Roosevelt. I’m a fan of Teddy’s. He was a lifelong birder and enthusiastic amateur naturalist. His efforts on behalf of wildlife and wild land are undeniable. He was the right man in the right place at the right time. But he did not invent conservation, nor do I think he was really the prime mover in that field. If that credit can be given to anyone in his generation, it belongs to someone else.

When Teddy was twenty-seven, he met that man. Teddy had just returned from six months on his nascent cattle ranch in the North Dakota badlands, recovering from the shock of the deaths of his mother, Mittie, and his wife, Alice, within twenty-four hours of each other on Valentine’s Day, 1884. On his return, he’d launched into a feverish period of writing that led to his book, Hunting Trips of a Ranchman, which appeared in July of 1885.

The book was generally well received, but there was one review that rankled Roosevelt. The editor of Forest & Stream, possibly the most influential outdoor periodical of the age, thought the book an excellent effort . . . with certain reservations:

“Mr. Roosevelt is not well known as a sportsman,” the editor wrote, “and his experience of the Western country is quite limited, but this very fact lends an added charm to the book. He has not become accustomed to all the various sights and sounds of the plains and the mountains, and for him all the differences which exist between the East and the West are still sharply defined. . . . We are sorry to see that a number of hunting myths are given as fact, but it was after all scarcely to be expected that with the author’s limited experience he could sift the wheat from the chaff and distinguish the true from the false.”[i]

George Bird Grinnell

Fuming at this insult to his experience and knowledge, Teddy stomped into the Forest & Stream premises at 40 Park Row in New York and demanded to see the editor. George Bird Grinnell invited him into his office. I’d like to have been a fly on the wall during that conversation.

Grinnell was nine years older than Roosevelt, a gap in age that made a huge difference in the experiences of the two men. Grinnell had first gone west in the summer of 1870 with a paleontological expedition organized by Yale University professor Othniel Marsh. On that trip, he saw the last of the great bison herds and made a buffalo hunt with the Pawnee.

In 1874, he rode with the George Custer and the Seventh Cavalry on a surveying expedition into the Black Hills, sacred land of the Lakota.

In 1875, Colonel William Ludlow invited Grinnell to join a survey expedition across Montana into what is now Yellowstone National Park. On that trip, Grinnell noted the rising tide of big game slaughter that would nearly eliminate bison, elk, deer, and pronghorn in the region. In 1876, Custer invited him to serve as naturalist on yet another foray into Sioux country, but the demands of Grinnell’s work at the Yale museum kept him from going.

Which is why he was not with his dear friend, Lonesome Charley Reynolds, chief of the Seventh’s Pawnee scouts, on the afternoon of June 25 as they fought a rearguard action at the ford of the Greasy Grass, giving their lives so that Marcus Reno and his command could gain the bluffs that saved them from the fury of the Sioux and Cheyenne.

Members of the 1870 Yale University expedition to Wyoming. (George Bird Grinnell stands third from left)

In the years that followed, Grinnell hunted extensively in the West and, in 1883, bought a ranch in Shirley Basin, where he spent much of his time over the next decade. He’d seen the last of the best of the western frontier.

Roosevelt quickly realized that there were few New Yorkers, few Easterners, who knew the West better than George Bird Grinnell. What began as a confrontation soon became a fast friendship.

By that time, Grinnell had already distinguished himself as the leading voice for conservation in the America of his time. His tireless campaigning in the pages of Forest & Stream had helped persuade Congress and the American people to give adequate protection to big game in Yellowstone National Park. He’d been a critical force in convincing states to establish game codes and wildlife agencies.

And his interests reached far beyond big game. Along with a handful of other naturalists, he’d watched the trends in several bird species with growing alarm.

The great auk, North America’s only penguin, had disappeared before the Civil War.

The Labrador duck, a waterbird with a taste for mussels, was probably also extinct before 1880.[ii]

The heath hen, the prairie grouse of the barren-ground openings along the northeastern coast, had disappeared from the American mainland by 1869.[iii]

The “great flocks of the gorgeous” Carolina parakeets “that formerly roamed over nearly all the eastern part of our country,” according to Arthur Cleveland Bent,[iv] had largely disappeared by the 1870s.

At the same time, Eskimo curlews, one of the most abundant shorebirds on the continent, were being shot by the wagonload, “the wagons being actually filled, and often with the sideboards on at that.” By the 1880s, they were on their way to extinction.[v]

Martha, the last living passenger pigeon

And the passenger pigeon— before settlement, there may have been as many passenger pigeons in North America as there are birds OF ALL SPECIES on the continent today. While reducing the unimaginable abundance of the passenger pigeon to a single estimate was impossible, one of the leading experts on the species believed there were between three and five billion passenger pigeons in America when the first Europeans landed.[vi] Grinnell was old enough to remember seeing a dogwood tree behind his house so full of passenger pigeons “that all could not alight in it, and many kept fluttering about while others fed on the ground, eating the berries knocked off by those above. . . . There were regular autumnal flights of pigeons up and down the bank of the Hudson River until 1873 or 1874. We boys killed a few, shooting them from the roof.”[vii]

By the time Roosevelt and Grinnell met in 1885, the passenger pigeon was in free fall. Laws to protect the bird were passed as early as 1862, a recognition of their decline, but the combination of indiscriminate killing and the wholesale clearing of old-growth deciduous forest was more than the pigeons could survive.

Both Grinnell and Roosevelt were undoubtedly aware of these, and other, shocking declines, but it was Grinnell, not Roosevelt, who had taken up the challenge of doing something about them. When Roosevelt left Grinnell’s office, he traveled west again to hunt and play cowboy for eight months before returning to New York to run as the Republican candidate for mayor.

In February 1886, Grinnell used the front page of Forest and Stream to call for a new organization to end “the fashion of wearing the feathers and skins of birds,” popular among stylish ladies of the age. “The Forest and Stream has been hammering away at this subject for some years,” he continued. “Legislation of itself can do little against this barbarous practice, but if public sentiment can be aroused against it, it will die a speedy death. . . . We propose the formation of an association for the protection of wild birds and their eggs which shall be called the Audubon Society.”[viii]

It was far from the first of Grinnell’s efforts on behalf of birds, both game and nongame. In 1883, a small group of ornithologists gathered to establish a national organization to support research and protection of birds. They called the new outfit the American Ornithologists’ Union. The founders of the union immediately voted to add another twenty-four noted students of ornithology as active members. Grinnell was near the top of that list.[ix]

Lilian Russell modeling extravagantly plumed hat, the fashion of the last 19th century in America.

The AOU wasted no time in advancing its goals in the conservation arena. Within two years, the leaders of the organization had convinced Congress to create the Division of Economic Ornithology, which, with the existing U.S. Fish Commission, would eventually become the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. At the same time, the committee on bird protection, with Grinnell as a prominent member, drafted a model law that could be used as a guide for state legislatures who wanted to protect birds. Much more on the model law in a few minutes. Still, the committee recognized that the AOU could do little to help birds without broad public support. Their response to that challenge has George Bird Grinnell’s fingerprints all over it. Trained zoologist, experienced naturalist, expert on the emerging debates over wildlife and wild land, editor, and prolific writer, Grinnell was an expert in the art of public outreach.

It’s hard to say who actually invented the idea that resulted in the Audubon Society. At least one other member of the committee had issued a public call for “the formation of bird protective societies.” Days after Grinnell’s formal solicitation for Audubon members in Forest and Stream, other AOU members contributed seven articles in a special supplement to Science magazine focused on the increasing slaughter of birds to provide feathers and entire skins for ladies’ hats.

“One thing only will stop this cruelty— the disapprobation of fashion,” the committeemen wrote. “Let our women say the word, and hundreds of thousands of bird-lives every year will be preserved.”[x]

Still, two things seem clear: first, that Grinnell named the new organization and, second, that he shouldered the entire responsibility for organizing and administering it. By May 1886, his office had received more than 5,000 pledges to protect birds. In August, the society was incorporated with Grinnell as the president pro tem. By the end of the year, Audubon had more than 300 local secretaries and nearly 18,000 members. In January of 1887, Grinnell published the first issue of Audubon magazine.

Over the next three years, nearly 50,000 people joined the society. With no membership dues or treasury, the load became unsupportable— in January of 1889, Grinnell announced that he was discontinuing the magazine “as its preparation calls for a good deal more labor than our busy staff can well devote to it.”[xi] With that, the de facto national headquarters of the organization had closed, and according to one of the AOU stalwarts, “the organized effort for bird protection” also seemed to have lost its momentum.[xii]

While tangible progress may have been lacking, ongoing commitment was not. The AOU members continued to reach out to other professionals in the field of ornithology and the general public, led by the redoubtable Grinnell, and the unending barrage of articles in popular magazines and technical journals fed the growing concern in America. The ideal that had emerged in Grinnell’s Audubon Society hadn’t died with his announcement— in fact, it was quietly growing into a political force.

——-

Harriett Lawrence Hemenway, co-founder of the Massachusetts Audubon Society. (Portrait by John Singer Sargent)

SOMETIME IN THE WINTER OF 1895-96, Harriett Lawrence Hemenway, a scion of a well-known Boston family who had married into another of Boston’s elite lineages, had finally had enough. Educated at Radcliff and raised by a famous abolitionist to speak her mind, Hemenway had been keeping up with the reports of carnage in the nesting rookeries to the south. Some sources speculate that it was an article by William Hornaday that set her off, but I suspect she’d been following the growing controversy for years. I wouldn’t be at all surprised if she had been one of the 50,000 members of Grinnell’s original Audubon Society.

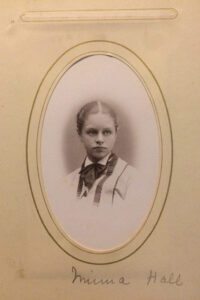

Whatever the proximal cause, she looked out on the bleak Boston winter and decided it was time to do something. She sat down with her friend and cousin, Minna B. Hall, and the two of them took up the challenge of ending the plume trade from the consumer’s end. They used their connections in Boston society to chat with the ladies of means about the immorality of decorating hats with the feathers and skins of birds that had been slaughtered as they tried to raise their young.

On February 10, 1896, Hemenway invited Minna and six other interested parties to her home to organize a state effort on behalf of birds. Nine days later, the Massachusetts Audubon Society was officially launched. The two women recruited William Brewster, the state’s most famous ornithologist and one of the leaders of the AOU, to serve as its first president. Harriett became one of the society’s vice presidents; Minna was appointed to the board of directors.

“We sent out circulars asking women to join a society for the protection of birds, especially the egret,” Hall said years later. “Some women joined and some who preferred to wear feathers would not join.” There weren’t many in that second category— at the end of the first year, the organization had 926 associate members and 385 school members.

Minna B. Hall, co-founder of the Massachusetts Audubon Society.

One of the new society’s highest priorities was “to influence other States to start Societies,” and its astounding success in that effort was tribute to the popularity of the idea that Grinnell had pioneered. Late in 1896, the state of Pennsylvania established its own Audubon Society, and in 1897, New York, New Hampshire, Illinois, Maine, the District of Columbia, Wisconsin, New Jersey, and Colorado followed.[xiii] By 1900, there were enough state Audubon Societies to justify a national conference, which was held, appropriately enough, in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Hemenway and Hall fought the good fight for conservation for the rest of their lives, which were considerable— Minna died in 1951 at the age of 92; Harriett lived to 102, dying in Boston in 1960.

There’s a story about these two I have to share. A few years before Minna died, Harriett, already in her nineties, confided to a friend that she thought Minna was working too hard— she was just too busy. At a concert some weeks later, Minna told a friend that she thought Harriett looked tired.

“She doesn’t know when to stop,” Minna said.

I wish I’d had the chance to know the two of them.

——-

AT THE BEGINNING, the epicenter of the bird protection movement lay somewhere on the East Coast, but the appeal of the concept reached across the country, even as far as Cheyenne.

In March of 1882, a young man came to town to take a draftsman’s job with the surveyor-general’s office. Born in 1856 to a farming family in eastern Iowa, Frank Bond grew up with an abiding interest in birds.

Frank Bond

Before he finished his master’s degree at the University of Iowa, he’d amassed a collection of more than 500 bird specimens, which he left to the university before coming west. In 1890, he was elected to the Wyoming House of Representatives for one term, and in 1895, he was hired as editor of the Wyoming Eagle.

Through those years, he continued his ornithological interests. He was accepted as a member of the American Ornithological Union in 1887 and published his first technical note in the union’s journal two years later. Because of that connection, he was aware of the AOU’s model bird law, a framework of restrictions designed to protect nongame birds, their nests, and eggs.[xiv] It was intended to provide guidance to state legislatures, which, at the time, had sole authority to protect birds and other wildlife. The AOU and Audubon societies throughout the country had been pressing state lawmakers to adopt the model law for more than a decade with little success.

Bond pressed for passage of the model law in Wyoming. Since the newspapers he edited were printed on high-acid paper, none of them have survived, but he must have used the daily to press his argument. His acquaintance with the legislators in the state certainly gave him the opportunity to make a case for the bill.

Early in 1901, Governor DeForrest Richards recommended that “some measure be passed guaranteeing protection for our song and insectivorous birds.” On Valentine’s Day, Wyoming’s version of the model law passed both houses.

Other states had passed measures that offered some protection to birds— according to Grinnell himself, New York adopted a version of the model law in 1886— but, on that date, no other state had followed the AOU guidelines in full. Wyoming the second state in the nation to back the AOU framework.

The second state in the nation.

Seven other states adopted similar laws in 1901, but Wyoming was a leader in the effort . . . thanks to Frank Bond.

Following that success, Bond announced a meeting to consider the formation of the Audubon Society of the State of Wyoming. An article in Bird-Lore, the national Audubon periodical, noted that, on April 29, 1901, “a crowd of enthusiastic ladies and gentlemen assembled in the parlors of the Inter Ocean Hotel”[xv] to organize the new group. “Bird lovers,” it concluded, “a term which will soon include all of the farmers and agriculturists of the country, if it does not already, will be gratified to learn that the Audubon Society started out with a membership of 900, the result of a few days’ work only.”

And here I have to pause to wonder what series of events blighted this heroic beginning. By rights, we should be celebrating the 123rd anniversary of Wyoming’s Audubon movement tonight, not just its fiftieth.

In any case, Bond was elected president of the fledgling society, and it must have been a bittersweet moment, since he probably already knew he’d be leaving Cheyenne that summer to join Teddy Roosevelt’s administration as chief of the Drafting Division of the General Land Office in Washington, D.C.

Pelican Island during nesting season.

Bond was aware of a small island on Florida’s Indian River that was a magnet for wading birds of all sizes and descriptions. It was owned by the government, and, as he considered the vast public domain still under federal control, he had an idea: a national refuge for birds. He committed the concept to paper, and it made its way up through the bureaucratic chain of command until it landed on President Roosevelt’s desk. Teddy liked it, and, in 1903, signed the executive order creating Pelican Island National Wildlife Refuge.

In his position with the Land Office, Bond was uniquely positioned to expand the refuge concept to other federal holdings that were particularly important to birds and other wildlife. He reached out to AOU and Audubon members across the country, toured many of the potential reserves, and built a list of new refuges for Teddy’s signature— fifty-one more of them by the end of his first term.

In 1911, the head of the new National Association of Audubon Societies praised Bond’s work on the refuge idea: “It was he who prepared the Executive Orders and important explanatory letters of transmittal to the President for the remaining fifty-one reservations. . . . No man, at this early period in the bird protection movement, can even estimate the value of these reservations to the rising generation, which is now taking up the burdens of human existence, much less foretell the blessings the increase in bird life will confer upon those who follow in the centuries to come.”[xvi]

Bond could well be called the father of the national wildlife refuge system. And no one remembers his name.

——

THERE’S A SHOPWORN HOMILY THAT’S MADE THE ROUNDS in management seminars for generations. I think it was first written down by a nineteenth-century Englishman who said he heard it from a Jesuit priest: “A man may do an immense deal of good,” he commented,” if he does not care who gets the credit for it.” Sometimes, the only difference between a piece of wisdom and a cliché is just how often it’s been repeated.

When I read the history of wildlife conservation covering the crucial sixty years between 1870 and 1930, I find George Bird Grinnell at every turn, a member of every committee, a mentor who framed enlightened national policy, an indispensable spokesman for the movement. An influential member of the AOU, the mind behind the Audubon Society, a founder of the Boone & Crocket Club, he is always there, and, just when the moment of success arrives, when the pictures are taken, and the laurels given, he takes two quiet steps to the rear and lets others take the credit.

I became aware of Harriett Hemenway and Minna Hall when I stumbled across their names footnoted in an obscure biography of another person. Dig as I might on the internet, I’ve found relatively little testament to their lives and contributions. When the time came to name a president of the Massachusetts organization they had built from scratch, they gave the office to a man of reputation and spent most of the rest of their lives in the trenches, always striving toward the goal, never caring who got the credit.

And Frank Bond. In 1903, a fashionable publishing company brought out a ponderous tome, Progressive Men of the State of Wyoming, a guide to the founders of the state who had won fame by their outstanding contributions to society. Frank’s twin brother, Fred, who served as the Wyoming state engineer and guided some of the state’s most ambitious irrigation projects, is mentioned prominently. Frank does not appear. In fact, the only real tribute to his work is the article in Bird-Lore, which outlines a career that has few parallels in American conservation. I don’t imagine Frank cared who got the credit.

These are by no means the only people of that era history has forgotten. There’s Gil Pearson, the Carolina farm boy who united the Audubon movement and led the national organization through its formative years. Mabel Osgood Wright, the woman who did in Connecticut what Hemenway and Hill did in Massachusetts, then went on to serve on the board of directors of the National Association of Audubon Societies for twenty years and eleven years as the editor of Bird-Lore, the precursor of Audubon magazine. Mrs. Mary Riner who took over the presidency of the Wyoming Audubon Society after Frank Bond left the state, and the thousands of other Audubon activists who served as officers and board members across the country. The hundreds of thousands of people who signed the Audubon pledge, joined the society, and lent political weight to the cause of conservation.

While there were prominent voices raised on behalf of America’s wildlife beginning as early as 1630, I think it’s fair to say that the true conservation movement did not begin with leaders. It rose out of the grass. The same can be said of most important social movements— they profit from great leadership, but they rise from a shift in public consciousness, public conscience. The movement creates the leader, not the other way around.

Theodore Roosevelt addresses a crowd in Colorado

I believe that was the case with the conservation movement in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Theodore Roosevelt is the face history has put on the conservation effort of that time. Certainly, it rose from a point of view he shared and was happy to advocate, but he was, first and foremost, a politician, occupied with gaining and wielding power. In the conservation movement, he recognized, not only a righteous cause, but a political opportunity he was happy to represent and exploit.

——

NEARLY A CENTURY AGO, the English essayist Aldous Huxley had this to say about our collective memory: “That men do not learn very much from the lessons of history is the most important of all the lessons that history has to teach.”[xvii] I hope we can glean at least something from the history our predecessors made, the legacy they left us.

The successes of the Audubon movement and the rest of conservation in its first thirty years were staggering. The model bird law was adopted across the country, followed by a succession of federal laws that culminated in the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, which protected migratory birds, game and nongame, across the entire continent. The conservation community created state and federal wildlife agencies that helped build the scientific foundation for wildlife management and hired the wardens needed to enforce the protection laws on the books. The national park system, the national wildlife refuge system, and the national forest system were all launched and rapidly expanded.

The impact on wildlife was heartening. While the passenger pigeon, Carolina parakeet, and heath hen were too far gone to be saved, other spectacular bird species were pulled back from the brink of extinction.

The trumpeter swan.

The whooping crane.

The snowy egret.

Thanks to the efforts of two generations of conservationists, few people remember that the wood duck was once thought to be beyond help. In 1901, Grinnell himself was pessimistic about the wood duck’s future: “Being shot at all seasons of the year they are becoming very scarce and are likely to be exterminated before long.”[xviii] What a gift to those of us who came after that this species was saved.

Greater sage grouse male displaying in southern Wyoming. Copyright 2020 Chris Madson.

There’s no doubt that these successes were due, in no small part, to the leadership Roosevelt and influential members of Congress provided over the decades. But there is also not a shred of doubt that these leaders would have gotten nowhere without the massive power of the citizen conservation movement— one important lesson the history of those times has to teach.

The years that separate us from those activists impart another somber lesson— the work of conservation is never done. In spite of the legacy of law, habitat protection, and science we’ve inherited from them, we have our own heath hens.

The Attwater’s prairie chicken clings to existence on a tiny sliver of native grassland along the Texas coast.

The lesser prairie chicken has been classified as threatened and even endangered on a corner of the High Plains that is almost entirely in private hands, a prairie landscape that has been plowed almost out of existence.

And, closer to home, the greater sage grouse continues its century-long slide toward oblivion, a victim of the pernicious fable that the sagebrush grasslands can be all things to all people.

The work is never done. But the good news from the past is that conservation rises from the grass. From us. The people of a future age may not remember who we were, but they will remember what we saved.

——————-

[i] Grinnell, G.B. 1885. “New Publications: Hunting Trips of a Ranchman”. Forest & Stream, July 2, 1885. https://archive.org/details/sim_forest-and-stream-a-journal-of-outdoor-life_1885-07-02_24_23/page/450/mode/2up

[ii] Chilton, G. (2020). Labrador Duck (Camptorhynchus labradorius), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole and F. B. Gill, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA.

[iii] Gross, Alfred O., 1928. The heath hen. Memoirs of the Boston Society of Natural History, Boston, MA.

[iv] Bent, A.C., 1964. Life histories of North American cuckoos, goatsuckers, hummingbirds, and their allies. Dover Publications, New York, NY.[v] Bent, A.C. 1962. Life histories of North American shorebirds. Dover Publications, New York, NY.

[vi] Schorger, A.W., 1973. The passenger pigeon: its natural history and extinction. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, OK. P.204.[vii] Reiger, John f. [ed.], 1985. The passing of the Great West: Selected papers of George Bird Grinnell. University of Oklahoma Prress, Norman, OK. P.11.

[viii] Grinnell, George Bird, 1886. “The Audubon Society”. Forest and Stream: A weekly journal of the rod and gun. Volume 26 (2): 41. February 11, 1886. https://archive.org/details/sim_forest-and-stream-a-journal-of-outdoor-life_1886-02-11_26_3/mode/2up

[ix] Anon., 1884. “The American Ornithologists’ Union”. Bulletin of the Nuttall Ornithological Club 8(4): 222-223. https://archive.org/details/bulletinofnuttal81883nutt/page/222/mode/2up?q=American+Ornithollgist%27s+Union

[x] Anon, 1886. “An appeal to the women of the country in behalf of birds”. Science 7(160S): 205. https://www.science.org/doi/epdf/10.1126/science.ns-https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.ns-7.160S.204

[xi] Grinnell, G.B., 1889. “Discontinuance of the ‘Audubon Magazine'”. Audubon 2(12): 262. https://archive.org/details/audubonmagazine02nati/page/262/mode/2up

[xii] Orr, Oliver H., Jr., 1992. Saving American Birds: T. Gilbert Pearson and the founding of the Audubon movement. University Press of Florida, Gainesville, FL. P.30. https://archive.org/details/savingamericanbi0000orro/page/30/mode/2up

[xiii] Packard, Winthrop, 1921. “The story of the Audubon Society: Twenty-five years of active and effective work for the preservation of wild birdlife”. Bulletin of the Massachusetts Audubon Society for the Protection of Birds, 5(8): 3-5. Boston, MA. https://books.google.com/books?id=v90UAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

[xiv] Anon, 1886. “Bird-laws”. Science 7(160s): 204. file:///Users/chrismadson/Downloads/science.ns-7.160S.202.pdf

[xv] Anon., 1901. ” The Audubon Society of the State of Wyoming”. Bird-Lore 3(4): 148. https://archive.org/details/sim_bird-lore_july-august-1901_3_4/page/148/mode/2up?q=Bond

[xvi] Pearson, T. Gilbert, 1911. “Some Audubon workers: Frank Bond”. Bird-Lore 13(3): 175-177. https://archive.org/details/sim_bird-lore_may-june-1911_13_3/page/176/mode/2up

[xvii] Huxley, Aldous, 1958. Collected Essays. Harper & Brothers Publishers, New York, NY. https://archive.org/details/205p-aldous-huxley-collected-essays/page/160/mode/2up?q=%22lessons+that+history+has+to+teach%22

[xviii] Grinnell, George Bird, 1901. American duck shooting. Field and Stream Publishing Company, New York, NY. p.142. https://archive.org/details/americanduckshoo01grin/page/142/mode/2up

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.