AS I’VE RUN OUT MY STRING OF YEARS, I’VE DEVELOPED A DEEPENING APPRECIATION FOR THE efforts of the people who fought the fight for the land long before we did. There’s an epigram that’s made the rounds for years. It’s been attributed to Mark Twain, although no one seems to be able to find it in his writing. Chances are good that it was synthesized by that famous writer, Anonymous, and like many things of his, it has a certain weight. “History may not repeat itself,” the saying goes, “but it rhymes.”

I’d like to consider a few of those rhymes, contained in the work of three men in our now-distant past, largely neglected today, who advocated the conservation of renewable resources like soil, water, wildlife, and wild land before the need for conservation was recognized by America at large. They were ahead of their time, which is, all too often, an uncomfortable place to be.

So, the text of this sermon comes from a source I seldom cite: the King James version of the Bible, specifically, the prophet Isaiah, chapter 40, verses 3 and 6:

“The voice of him that crieth in the wilderness . . . And he said, What shall I cry? All flesh is grass, and all the goodliness thereof is as the flower of the field.”

I am, perhaps, to be forgiven if this biblical passage has stuck in the back of my mind over the course of a career that has spanned more than forty years. Back there in the early 1970s, when my cohort of wildlife people were finishing graduate school, it seemed that the nation was poised on the verge of a wholehearted commitment to the precept of wise use. The Clean Water Act with its migratory bird rule, LWCF, the Wilderness Act, NEPA, wild and scenic rivers, ESA, the Fish and Wildlife Coordination Act, ANILCA, the return of CRP under the 1985 Farm Bill, Sodbuster, Swampbuster, NAWMP, NAWCA— Americans were unanimous in their support of conservation of wildlife, both game and nongame, along with a sensible approach to the management of renewable natural resources.

Or so it seemed. As the last forty years have proven, the apparent consensus on conservation and the environment was far, far more fragile than my generation in the profession thought. We’ve watched as the political and financial support for conservation has waned, as traditional coalitions have dissolved, as former allies have declared holy wars against one another, and as special interests have exploited the disarray to begin the job of dismantling the regulatory framework that defined conservation in the twentieth century.

The wildlife profession has been engaged in a fighting retreat for a generation, and the advocates of enlightened conservation find themselves isolated, with little political leverage, our recommendations and objections like “the voice of him that crieth in the wilderness.”

In such times, I think it’s comforting— and often instructive— to look back over our shoulders and attend to other voices, raised in other times, who also cried out in a wilderness of indifference.

Voices like George Catlin’s.

—————–

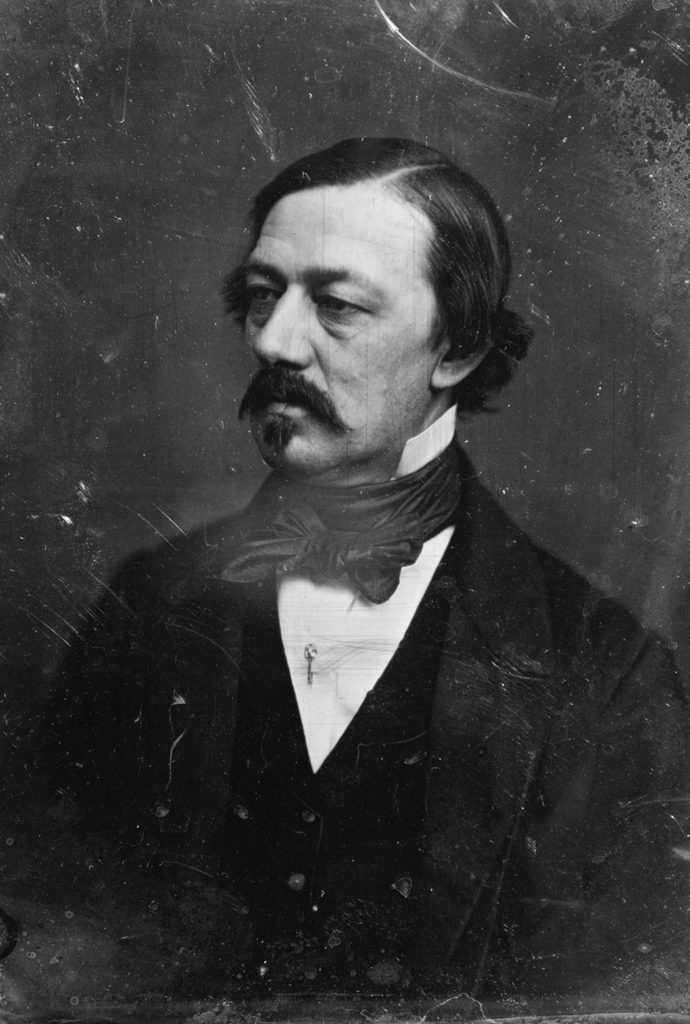

CATLIN was crazy. Scion of a middle-class Pennsylvania family, he trained as an attorney, following in his father’s footsteps, and spent two or three years comfortably practicing law before he sold all his law books to buy paint and canvas. With no formal training, he set out to support himself as a portrait painter in Philadelphia. He was far from a brilliant artist, but he managed to make ends meet for several years, and if that was as far as his ambition had taken him, he would have faded into obscurity.

Then, one summer afternoon, a delegation of Winnebagos passed through Philadelphia on their way from Wisconsin to the Great White Father’s house in Washington, D.C., to complain about illicit lead miners on their land. Catlin was transfixed by their costume and bearing. As he told it, he made up his mind on the spot: “The history and customs of such a people, preserved by pictorial illustrations, are themes worthy of the life-time of one man, and nothing short of the loss of my life, shall prevent me from visiting their country, and of becoming their historian.”[i]

Friends and family tried to reason with him. “I broke from them all— from my wife and my aged parents,” he wrote, and “with these views firmly fixed— armed, equipped, and supplied, I started out in the year 1830 and penetrated the vast and pathless wilds of the great ‘Far West’ with a light heart.”[ii] He would be gone for eight years.

In St. Louis, he managed to hitch a ride with William Clark, then the Indian commissioner for the region, as Clark traveled up the Mississippi for a council with several tribes at Prairie du Chien. Along the way, Catlin met a dozen of the tribes gathered along the upper reaches of the river and got his first taste of what was then the American frontier.

Back in St. Louis, he began looking for ways to get farther west and was lucky enough to find a new form of transportation. He booked passage on the steamboat Yellowstone, bound for the mouth of the Yellowstone River on the upper Missouri, where he found what he’d been looking for:

“. . . the interminable and boundless ocean of grass-covered hills and valleys . . . where the bison range, the elk, the mountain-sheep, and the fleet-bounding antelope— where the magpie and chattering paroquettes supply the place of the red-breast and the blue-bird— where wolves are white and bears grizzly— where pheasants are hens of the prairie, and frogs have horns!”[iii]

He spent time with the Crow, the Mandan, the Sioux, the Iowa, the Konza, the Pawnee, and then, down along the Arkansas River, with the Osage, the Cherokee, the Comanche, and back north into Minnesota, with the Chippewa, the Menominee, the Winnebagos, the Sac and Fox— fifty tribes according to one count. By the time he returned to the East, he’d seen most of the Great Plains, and somewhere in his travels, he’d come up with a big idea.

“This strip of country, which extends from the province of Mexico to lake Winnepeg on the North, is almost one entire plain of grass. . . . It is here, and here chiefly, that the buffaloes dwell; and with, and hovering about them, live and flourish the tribes of Indians, whom God made for the enjoyment of that fair land and its luxuries.

“It is a melancholy contemplation for one who has traveled as I have, through these realms, and seen this noble animal in all its pride and glory, to contemplate it so rapidly wasting from the world, drawing the irresistible conclusion too, which one must do, that its species is soon to extinguished, and with it the peace and happiness (if not the actual existence) of the tribes of Indians who are joint tenants with them, in the occupancy of these vast and idle plains.

“And what a splendid contemplation too, when one imagines them as they might in future be seen, (by some protecting policy of government) preserved in their pristine beauty and wildness, in a magnificent park, where the world could see for ages to come, the native Indian in his classic attire, galloping his wild horse, with sinewy bow, and shield and lance, amid the fleeting herds of elks and bison. What a beautiful and thrilling specimen for America to preserve and hold up to the view of her refined citizens and the world, in future ages! A nation’s Park, containing man and beast, in all the wild and freshness of their nature’s beauty!

“I would ask no other monument to my memory, nor any other enrolment of my name among the famous dead, than the reputation of having been the founder of such an institution.”[iv]

It had been the reason he’d set out, and the things he’s seen over the thousands of miles, back and forth across the Great Plains, had only deepened his conviction that this unique North American wilderness should be somehow preserved. All that was left was to use his art to convince the rest of the nation. He spent most of the rest of his life in that attempt, touring the United States with the paintings and artifacts in what he called his “Indian gallery.” The admission price wasn’t enough to support him, so he appealed to Congress, asking them to buy the collection. Congress declined.

Short of funds, he packed up the gallery and headed to Europe where the exhibition generated a reasonable amount of money but not enough to keep him clear of debt. Back in the states, he sold the collection to an industrialist, then began reproducing many of the paintings from memory to support his family. Hungry for the wilderness of his youth, he made extensive trips to Central and South America along with another trip back to the American West.

He died in Jersey City, New Jersey, in the winter of 1872 in the knowledge that his worst predictions concerning the native peoples and wildlife of the Great Plains were rapidly coming true. It would be another seven years before the collection of his art and tribal artifacts were finally donated to the Smithsonian Institution. But just before he died, in the spring of 1872, the nation granted his greatest wish— a “magnificent park,” forerunner of a revolutionary “protecting policy of government” that would set the standard for the world.

—————

WHILE Catlin was crisscrossing the wilderness of the Great Plains, another man of his generation was doing his best to build a life in the much more settled landscapes of Vermont— George Perkins Marsh. The son of a prominent lawyer and Congressman, Marsh attended Dartmouth College, where he graduated at the head of his class at the age of nineteen, then passed the bar exam as Catlin had and set up a law office in Burlington.

Like Catlin, he seemed to have had little taste for the law. After the death of his partner in 1832, his business steadily declined— he closed the office ten years later and launched his campaign for a Congressional seat. He won the election in 1843 and spent the next six years in Congress. The contacts he made in Washington eventually led to an extended career as a diplomat, first as the U.S. minister to Turkey, then as minister to Italy.

From his earliest boyhood, he’d shown a deep interest in the relationship between people and the land. He saw that relationship through two, often conflicting lenses. On one hand, the Calvinist philosophy he had absorbed as a boy remained with him all his life. Unlike Catlin and another contemporary observer of the natural world, Henry David Thoreau, Marsh had little use for wilderness.

In a speech in 1847, he argued that “in North America, the full energies of advanced European civilization were brought to bear on a desert continent, and it has been but the work of a day to win empires from the wilderness. . . . This marvelous change has converted unproductive wastes into fertile fields and filled with light and life the dark and silent recesses of our aboriginal forests and mountains.”[v]

He believed that wildlife was more abundant in areas where the primeval forest had been interspersed with small farms, that the New World was better off for the crops and animals that had been introduced from the Old, and that the waves of emigrants sweeping westward across the continent were actually a pacifying influence.

“The arts of the savage are the arts of destruction,” he believed. “Civilization,” he argued— against all the bloody evidence on both sides of the Atlantic, even then— “is at once the mother and the fruit of peace.”[vi]

In many of his opinions, he was very much a man of his time.

But he was also a keen observer. In that same speech— in 1847— he anticipated a problem that no one else had even considered:

“Though man cannot at his pleasure command the rain and sunshine, the wind and frost and snow, yet it is certain that climate itself has in many instances been gradually changed and ameliorated or deteriorated by human action. The draining of swamps and the clearing of forests perceptibly affect the evaporation from the earth, and of course the mean quantity of moisture suspended in the air. The same causes modify . . . the power of the surface to reflect, absorb and radiate the rays of the sun, and consequently influence the distribution of light and heat, and the force and direction of the winds.”[vii]

He’d watched as the timber had been cleared indiscriminately from the watersheds of eastern Vermont, and he’d seen the results:

“Steep hill sides and rocky ledges are well suited to the permanent growth of wood, but when in the rage for improvement they are improvidently stripped of this protection, the action of sun and wind and rain soon deprives them of their thin coating of vegetable mould, and this, when exhausted, cannot be restored by ordinary husbandry. They remain therefore barren and unsightly blots, producing neither grain nor grass, and yielding no crop but a harvest of noxious weeds. . . . The vernal and autumnal rains, and the melting snows of winter, no longer intercepted and absorbed by the leaves or the open soil of the woods, flow swiftly over the smooth ground, washing away the vegetable mould as they seek their natural outlets, fill every ravine with a torrent, and convert every river into an ocean. There is reason to fear the valleys of many of our streams will soon be converted from smiling meadows into broad wastes of shingle and gravel and pebbles, deserts in summer, and seas in spring and autumn.”[viii] George Perkins Marsh . . . in 1847.

Thanks to his diplomatic assignments, Marsh had the chance to travel through much of the western Mediterranean, where he saw the lasting effects of millennia of intensive farming and overgrazing: the salt-poisoned soils of the Fertile Crescent, the eroded hills where the vaunted cedars of Lebanon had once grown, the ravaged hillsides of north Africa and Italy, still showing the scars of wounds inflicted by the farmers of the Roman Empire soon after the birth of Christ.

The examples of the Old World and the trajectory of land use in America weren’t lost on Marsh. He began work on a detailed analysis of land management, the culmination of thirty years of observation and largely ineffective proselytizing. It was massive— 465 pages that appeared in 1864. He called it Man and Nature: Or Physical Geography as Modified by Human Action.

Much of his Calvinist confidence in civilized man seems to have evaporated in his masterwork, no doubt as a result of his experiences in Europe and the rapidly accelerating destruction that was already apparent in America.

“Man has too long forgotten that the earth was given to him for usufruct alone, not for consumption, still less for profligate waste,” he wrote. “Man is everywhere a disturbing agent. Wherever he plants his foot, the harmonies of nature are turned to discords. The proportions and accommodations which insured the stability of existing arrangements are overthrown. Indigenous vegetable and animal species are extirpated, and supplanted by others of foreign origin, spontaneous production is either forbidden or restricted, and the face of the earth is either laid bare, or covered with a new and reluctant growth of vegetable forms, and with alien tribes of life. These intentional changes and substitutions constitute, indeed, great revolutions; but vast as is their magnitude and importance, they are insignificant in comparison with the contingent and unsought results which have flowed from them.”[ix]

A retired medical doctor, Franklin B. Hough, read Man and Nature soon after it hit the streets and was deeply impressed. As the man in charge of the 1855 and 1865 census in New York state, he’d worked through data on shrinking timber supplies and found the numbers alarming. He reported them in an address to the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Portland, Maine, in 1873. The day after his speech, the association voted to approach Congress “on the importance of promoting cultivation of timber and preservation of forests.”[x] Three years later, Hough was appointed to begin a study of the condition of American forests, and his report led to the creation of the Division of Forestry in 1881, forerunner of the U.S. Forest Service.

Marsh died the next summer. He lived just long enough to see a lifetime of advocacy validated in the creation of the Forest Service. It would be another fifty years before the federal government translated his concerns over soil erosion into action with the establishment of the Soil Conservation Service— his warnings about the environmental and political consequences of large-scale irrigation were never taken seriously. And his passing thoughts on climate? Ignored at the time, forgotten for a century and a half, and still locked in political paralysis today.

Crying, crying in the wilderness . . .

———————

THERE is a third man of this generation who spoke to a wide audience during his life and has been largely forgotten since. Henry William Herbert was born in England to the offspring of nobility. His father was the unlucky third son of the Earl of Carnarvon; his mother, the daughter of Joshua Allen, fifth Viscount of County Kildare in Ireland. With no hope of inheriting title or estate, the father

trained as an attorney, then turned to religion and died as the Dean of Manchester Cathedral, the income from which allowed his son to gain an outstanding education at Eton and Cambridge while he nursed an abiding sense of having been somehow cheated out of a position among the British elite.

Soon after he graduated, Herbert left England to escape debt. He went first to Brussels, then Paris, and finally to New York in 1831, where he took a position teaching Greek in a fashionable prep school while he began writing novels and historical studies. To fill in the financial gaps between books, he wrote for several magazines, often focusing on hunting and fishing under the pseudonym Frank Forester.[xi]

He was by no means the first writer to advance the code of outdoor sport as it was understood by the aristocracy of Britain and Europe, but he was almost certainly the most influential.

America was, he thought, a paradise:

“There is, perhaps, no country in the world which presents, to the sportsman, so long a catalogue of the choicest game, whether of fur, fin, or feather, as the United States of North America; there is none, certainly, in which the wide-spread passion for the chase can be indulged, under so few restrictions, and at an expense so trifling.”

But he was quick to point out that this state of affairs was at risk.

“All this, notwithstanding, it is to be regretted that there is no country in which . . . the gentle craft of Venerie is so often degraded into mere pot-hunting; and none, in which, as a natural consequence, the game that swarmed of yore in all the fields and forests, in all the lakes, rivers, bays, and creeks of its vast territory, are in such peril of becoming speedily extinct.”[xii]

Some of this, he saw, was due to the thriving market in wild game, which encouraged every farmer’s son to shoot everything he could, whenever he could. “Knowing nothing, and caring less than nothing, about the habits or seasons of the birds in question, he judges naturally enough that, whenever there is a demand for the birds and beasts in the New York markets, it is all right to kill and sell them. And thanks to the selfish gormandizing of the wealthier classes of that city, there is a demand always.”[xiii]

But the problem reached far beyond commercial traffic in game, he knew. The vast majority of American hunters knew nothing about the animals they hunted— whether they migrated, when they courted and tended young, how many offspring they produced. Without that understanding, too many of them shot as many as they could at any season of the year. Forester pointed out impacts of that unrelenting pressure that were already obvious in the 1830s— the rapid decline of the heath hen, the local extirpation of the wild turkey and white-tailed deer. As Forester saw it, the hunter had a responsibility to know his quarry and conserve it, and he pounded that message home in his writing.

There had been efforts to control hunting of some high-profile species long before Forester’s arrival in America. New York adopted its first deer season in the mid-eighteenth century,[xiv] and the state adopted a law protecting the heath hen in 1791.[xv] Such statutes, Forester believed, “are intended solely to protect the animals in question, during periods of nidification, incubation, and providing for the youthful broods.”[xvi] The problem, as he saw it, was that these laws “emanated from the dwellers in cities,”[xvii] which encouraged the rural majority to ignore them. Without adequate enforcement, it was clear that regulations would not stem the carnage.

Forester hammered on these issues with a consistency and authority that encouraged more and more people to join the ranks of self-proclaimed “sportsmen.” At the same time, the local extinction of game along the East Coast emphasized the seriousness of the problems facing America’s wildlife.

Had Forester lived as long as Catlin and Marsh, he would have seen the first fruits of his labor. In 1871, Congress created the U.S. Fishery Commission to begin the job of rebuilding dwindling populations of game fish. In 1885, the Division of Economic Ornithology, forerunner of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, came into being. Two years later, Theodore Roosevelt and George Bird Grinnell launched the Boone and Crockett Club, a group of patrician easterners who were prime movers in drafting and enacting laws like the Lacey Act and sweeping new federal programs like the national wildlife refuge system.

Never a contented man, Forester seemed to have great hope for a change in his life when he married for the second time in 1858. He and his bride had just moved into his cottage in rural New Jersey when he was called away on business. While he was gone, a woman came to visit the new Mrs. Herbert and filled her in on the gossip concerning her husband, his rumored violent tendencies and his reported need for cash. Without waiting to confront him, she packed and left.

It was, apparently, the last straw for a man who had spent most of his life in a battle with depression. Late on the night of May 16, 1858, he excused himself from a conversation with a close friend, went into the next room, and shot himself. He was fifty-one.

In the letter he left behind, he asked the members of the press to “let the good that I have done, if any, be interred with my bones; let the evil also.”[xviii] A strange request, it seems, and one that, by accident more than intention, was granted. The memory of his real or imagined sins has long since faded, along with the substantial credit he deserves for mobilizing hunters and anglers in the service of conservation. Only the legacy of his pioneering leadership in the community of American hunters has survived. Another voice in the wilderness . . .

———————

THERE were a few others in this generation who saw the situation in America more or less the same way these three men did and took every opportunity to mount the argument that the nation needed to change its attitude toward the land. But, in the first half of the nineteenth century, the nation wasn’t listening. I suspect some of the people of that time believed the natural resources they consumed were infinite; a few saw the growing evidence of the damage that was being done but didn’t believe they could change the course of events. And a great many simply didn’t think about the impact of what they were doing or where their single-minded pursuit of profit ultimately led.

Sylvan Lake, Montana, Beartooth Wilderness, Montana. (Photo copyright 2017 Chris Madson, all rights reserved.

The shift, when it came, seems to me to have been the result of two forces. One was the undeniable proof of the landscape-scale destruction that was spreading west with civilization. More and more people could see it out their back doors.

The second was the power of the message a tiny group of pioneering conservationists persisted in spreading. It was that message that gave focus to growing doubts and reassured people who might otherwise have believed they were alone in their assessment of the developing problem. The second half of the nineteenth century produced the greatest leaders the conservation movement has ever seen, but I think it’s important to recognize they were as much an effect as a cause. The movement itself rose, with steadily increasing power, out of the grassroots.

My feeling is that this generation of wildlife professionals finds itself in a situation remarkably similar to the one Catlin, Marsh, Forester and their cohort faced almost 200 years ago. We’ve been talking, remarkably few Americans have been listening. Maybe this is a holdover from the 1970s, when it felt like we had all this under control. Or maybe it’s some sort of weird swing of the pendulum, back to a time when the nation was almost entirely controlled by the captains of industry. Whatever the cause, it has led us dangerously close to the precipice of environmental disaster.

I certainly can’t deny that, from the standpoint of wildlife conservation and the broader issues of environmental health, these are dark times, possibly even darker than the circumstances the nation faced in the middle of the nineteenth century. Any light I see at the end of the tunnel could well be just an oncoming train.

But here, I have to express a personal article of faith. It takes dark times to rouse Americans, and I believe these have been dark enough for long enough to do the trick. The people are starting to wake up, as they did in the years following the Civil War. The change in sentiment in those years resulted in our first national park, national forest, national monument, national wildlife refuge; the first laws against water pollution; the first widespread enforcement of hunting regulations; the removal of wildlife from the market, the recovery of the wood duck, trumpeter swan, elk, pronghorn, white-tailed deer; international protection of songbirds, shorebirds, and waders, and on and on and on.

It was startling— a revolution— driven, in part, by harsh necessity, and, in no small measure, by the tireless efforts of people who invested their entire lives in making it happen.

There’s no doubt— we live in different times. We’ve lost the margin of safety that was still in our grasp in the nineteenth century, and frankly, I don’t know whether we can prevail in the face of the crisis we’ve created. But before we can even begin to solve the problems that face us, we need broad agreement on the nature— and seriousness— of those problems. Over the last forty years, the wildlife profession has struggled to engage the mainstream of the American public, even at that elementary level.

I think that’s beginning to change. Conversations that, twenty years ago, were the province of academics and other professionals at the margins of society are merging into the

Drilling rig in the Green River basin, Wyoming. (Photo copyright 2015, Chris Madson, all rights reserved)

mainstream— discussions of climate change; sustainable agriculture; plummeting populations of mammals, birds, herptiles, fish, even insects; clean water; declining aquifers, instream flow. The same influences that changed the minds and hearts of other generations of America in other times are at work today. There is undeniable proof of landscape-scale destruction, in the evening news, on Facebook, and right out our back doors. And there is the undeniable power of the message that motivated professionals, like the ones in this room, persist in spreading. It gives focus to growing doubts and reassures people who might otherwise believe they are alone in their concern.

In 1938, the American poet Archibald MacLeish wrote a free-verse narrative that was intended to accompany the Depression-era photographs of Dorothea Dix and other contributors to the WPA. At the end of that poem, MacLeish reflected on the central role the American continent played in the rise of the American character:

“We wonder whether the great American dream

Was the singing of locusts out of the grass to the west and the

West is behind us now;” he wrote.

“The west wind’s away from us.

We wonder if the liberty is done;

The dreaming is finished.

We can’t say.

We aren’t sure.

“Or if there’s something different men can dream

Or if there’s something different men can mean by

Liberty. . . .

Or if there’s liberty a man can mean that’s

Men: not land.

We wonder.

We don’t know.

We’re asking.”

I believe that a substantial part of what it means to be an American is not men, but the land. And I believe that, somewhere between MacLeish and today, most Americans lost sight of that fundamental truth. The planet is in the process of reminding us. I believe Americans will be recalled to the duty they owe the land, and the grassroots will rise once again.

History may not repeat itself, but when I look back over the record of the struggle for conservation in America, I can hear the rhyme.

This is the text of a speech delivered at the Central Mountains and Plains Section of The Wildlife Society. My thanks to the organizers for providing the motivation to crystallize some of these thoughts.

[i] Catlin, George, 1842. Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs, and Condition of the North American Indians. Volume I. Wiley and Putnam, New York, NY. p.2.

[ii] ibid, p.3.

[iii] Ibid, p.60.

[iv] ibid, pp. 261-262.

[v] Trombulak, Stephen, C. (ed) 2001. So Great a Vision: The Conservation Writings of George Perkins Marsh. Middlebury College Press, Hanover, NH. p.2

[ix] Marsh, George P., 1864. Man and Nature: Or Physical Geography as Modified by Human Action. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA. p.36

[x] Steen, Harold K., 2004. The U.S. Forest Service: A History. University of Washington Press, Seattle, WA. pp 9-10.

[xi] Forester, Frank, 1864. Frank Forester’s Field Sports of the United States and British Provinces of North America. W.A. Townsend, New York, NY. Memoir of the author.

[xiii] Ibid, p.21.

[xiv] Trefethen, James, 1975. An American Crusade for Wildlife. Winchester Press, New York, NY. p.40.

[xv] Gross, Alfred O., 1928. The Heath Hen. Boston Society of Natural History, Boston, MA. p.496.

[xvi] Frank Forester’s Field Sports, op cit., p. 19.

[xviii] Ibid, xxx11.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.