THERE’S A POEM THAT’S HAUNTED ME MUCH OF MY ADULT LIFE.

Many years ago, my mother sent me a fragment of it— just five or six lines— that she’d found in a magazine somewhere. I kept the clipping on a bulletin board above my desk, but it tore loose from its moorings during an office move and disappeared along with the attribution, the author, and any hint of a connection to the broader context. In the years that followed, the verse kept coming back to me, a jumbled version of the words emerging in moments when the walls seemed to be closing in.

At one point, I called the chair of the state university’s English Department, hoping for guidance. That patient, sympathetic soul heard me out and, unable to identify the garbled passage I quoted, sent me on to a colleague at the University of Indiana. It was heartening to talk with people whose love affair with words is as passionate as my own, people who understood how frustrating it can be to find a passage that speaks so eloquently and then lose it. They dug through quaint and curious volumes of forgotten lore; they made inquiries of their own and suggested other avenues for the search, but, in the end, they couldn’t help.

At long last, it was the rise of the internet that unearthed the source. I entered the verse as I remembered it— no hits. I cut out a phrase or two I wasn’t sure of— still no hits. Finally, I used just two words, “men” and “freedom,” and there it was.

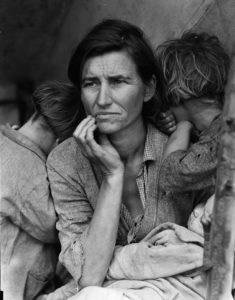

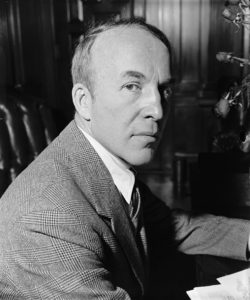

The work was “The Land of the Free” by Archibald MacLeish. MacLeish, a poet with a law degree from Harvard, ambulance driver and artillery officer in the First World War, one of America’s Lost Generation in Paris during the 1920s, and witness to the crash of 1929 and the Great Depression. In the late 1930s as the smothering gray clouds of the Dust Bowl were beginning to settle, he sat down to draft an accompaniment to a collection of eighty-eight photographs of the era made by Dorothea Lange and other visual geniuses who worked with the Farm Security Administration to document the common man’s view of the decade. The words he set down as companions to their

images were an anthem to the suffering of a generation of common people and an expression of their new-found doubt:

“We wonder whether the great American dream

Was the singing of locusts out of the grass to the west and the

West is behind us now;

The west wind’s away from us

We wonder if the liberty is done:

The dreaming is finished

We can’t say

We aren’t sure

Or if there’s something different men can dream

Or if there’s something different men can mean by Liberty. . . .

Or if there’s liberty a man can mean that’s

Men: not land

We wonder

We don’t know

We’re asking”.

Doubt, born of hard times. And, braided through the verse, a query that has defined generations of the American experience: “We wonder . . . if there’s liberty a man can mean that’s Men: not land.”

We’re a long, long way from any time as hard as the Dirty Thirties. Hardly anyone among us lived through those trials or the cataclysm of the second Great War that followed. In nearly every way imaginable, the vast majority of us are pampered beyond the wildest imaginings our grandparents might have cherished for us.

And yet there is this vague feeling of being restrained. Confined. Obstructed. Powerless. I suspect there’s nothing new in the sensation; in fact, I think it’s been a major force in the flow of our history, possibly even the prime mover— a sensation so powerful that it led generations to pack their meager belongs and take the great gamble, heading west, always west, through the merciless storms of the North Atlantic, across the Alleghenies, across the Mississippi and Missouri, across the great grasslands and deserts, the ice-bound ramparts of the Rockies, the Sierras, the Coast Range, and on into the trackless wastes of the Pacific. Generation after generation, looking for that ineffable commodity Daniel Boone called “elbow room.”

This was not, at its heart, an antisocial impulse; in fact, community was a common theme in the great emigration. Hospitality was one of its most cherished traditions. More often than not, contact with other people was a spice that flavored the quiet of day-to-day routine. But it was the quiet itself, born of space, of “elbow room,” that nourished our sense of freedom.

There are revolutionaries who argue that overweaning government is the thief that has deprived us of our freedom. While there may be a grain of truth in that observation, I see the growth of rules and regulations as a symptom, not a cause. A wise friend of mine once observed that “freedom is a finite commodity; how much you have depends on how many people you have to split it with.” My freedom to swing my fist stops at the end of my neighbor’s nose, so my fist-swinging is bound to be limited by the number of neighbors I have and how close we are together. It seems my friend was right— at a practical level, freedom often becomes a simple question of real estate— and I find I barely have room to raise my voice, let alone my fist. I have nowhere left to go.

Thomas Jefferson assured us that we were all endowed “with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” Tom also harangued an infant nation into putting up the money for the Louisiana Purchase. I suspect he’d smile in agreement at MacLeish’s words: “We looked west from a rise and we saw forever.”

That was the view from Jefferson’s time. He is to be forgiven for failing to imagine the view from the other side of forever. Elsewhere in “The Land of the Free,” MacLeish captured it:

“Now that the land’s behind us we get wondering

We wonder if the liberty was land and the

Land’s gone: the liberty’s back of us. . . .

We can’t say

We aren’t certain

We’re asking . . .”

There are times when faith gives way and doubt rises. Times like these. Is the liberty done, the dreaming finished? I’m not sure. I don’t know. I’m asking.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.